For nearly a decade, Nigerians have lived with inflation as a permanent affliction. Prices rarely stood still, rising faster than wages, eroding savings, and fuelling public distrust in every government pledge of stability.

Following President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s reforms, inflation surged to 34.2 percent by June 2024, the highest since Nigeria’s return to democracy in 1999, reflecting the immediate shock from subsidy removal and the naira float.

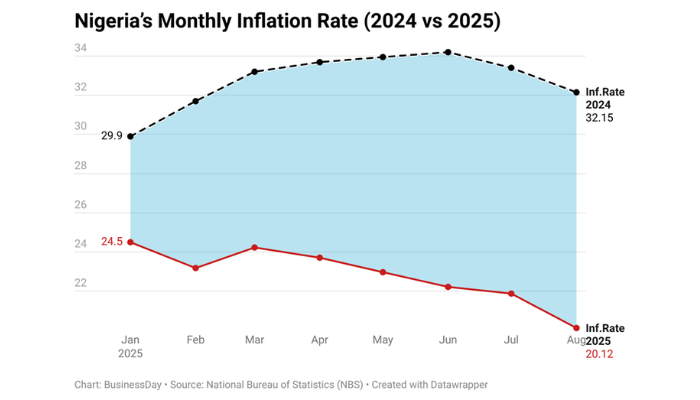

“Yet just a year later, the official story looked different. By July 2025, inflation had slowed to 21.8 percent and further declined to 20.12 percent in August.

The Independent Media and Policy Initiative (IMPI), in a report this month, called it a “disinflationary dispensation” with prices still rising, but at a slower pace. It was presented as proof that Tinubu’s gamble was beginning to pay off and that the economy’s resilience had been underestimated.

The tension lies here: policymakers talk of progress, but citizens still struggle to buy food and pay fares. Whether this slowdown is a genuine turning point or a statistical mirage remains the defining question.

A rare deceleration

Disinflation is rare in Nigeria’s economic history. Analysis by IMPI shows that over the past decade, prices have usually moved in one direction: up. The exceptions were 2017 and 2018, when inflation briefly slowed after the 2016 currency crisis.

The 2025 slowdown is sharper. From 24.5 per percent in January to 20.12 percent in August, inflation dropped by about 18 percent, the steepest mid-year deceleration in more than a decade. “Unlike 2020–2024, when inflation consistently accelerates, 2025 is shaping up as a genuine outlier,” IMPI notes.

Three factors explain the trend. First, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) has kept its policy rate at 27.5 percent, one of the highest in Africa. That has curbed speculative lending and slowed demand.

Second, the naira, after its sharp fall in 2023–2024, has stabilised in a band of N1,501–N1,530 per dollar, easing import cost pressures.

Third, better harvests and relative calm in food-producing regions have slowed food inflation, the single biggest driver of Nigeria’s consumer price index.

Scepticism persists

Not everyone is convinced. Critics argue that the apparent slowdown reflects technical changes rather than real relief. In February 2025, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) rebased its inflation basket, updating weights and the reference year.

“You don’t eat rebasing,” says a former opposition senator. “Nigerians don’t feel any price cuts. Tomatoes, rice, and transport are still more expensive than last year.”

This skepticism is echoed on the streets. Market traders in Lagos and Kano describe shrinking sales. Families cut food portions. For wage earners, disinflation has not meant cheaper goods, only slower price hikes on already inflated costs.

The divergence between statistics and lived reality fuels distrust. As one civil society activist put it: “The government celebrates falling inflation, but ordinary Nigerians celebrate when food becomes affordable. Until that happens, the reforms will not win hearts.”

Read also: Slowing inflation drives mixed expectations as MPC decides on rate today

Household consumption collapse

IMPI’s report underscores this point by tracking household spending. In Q1 2024, consumption fell 42 percent year-on-year. In Q2, it collapsed almost entirely, down 99 percent quarter-on-quarter. The subsidy removal and currency float hammered real incomes, forcing households to prioritise basic needs.

By 2025, signs of recovery are emerging. Statista projects consumer spending at $122 billion this year, with household disposable income per capita rising to $604. Food and beverage spending per head is forecast at $319.

The rebound reflects easing inflation, higher state wages, and expanded business activity. But recovery remains uneven, with urban households faring better than rural ones.

The PMI signal

One way to gauge whether disinflation is translating into real activity is the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI). After months below 50 signalling contraction, the PMI climbed above that threshold in October 2024. By August 2025, it reached 54.2, marking nine consecutive months of expansion.

Stanbic IBTC, which surveys the CBN, attributed the rise to stronger customer demand, new orders, and modest job creation. Importantly, input cost inflation slowed to its weakest pace since 2020, while output prices moderated for the fourth straight month.

“Disinflation is not just in the data; it is now visible in corporate cost structures,” says a Lagos-based investment banker. “Firms are adjusting prices, hiring cautiously, and clearing backlogs. That is what you expect in a stabilising economy.”

Policy discipline matters

IMPI credits the CBN’s hawkish stance as crucial. By holding the policy rate at 27.5 percent, the central bank restrained speculative forex trading and dampened credit demand.

At the same time, improved foreign exchange inflows from oil, remittances, and non-oil exports have anchored the naira. With reserves rising above $41 billion in September 2025, up $5 billion year-on-year, the CBN has room to intervene to smooth volatility.