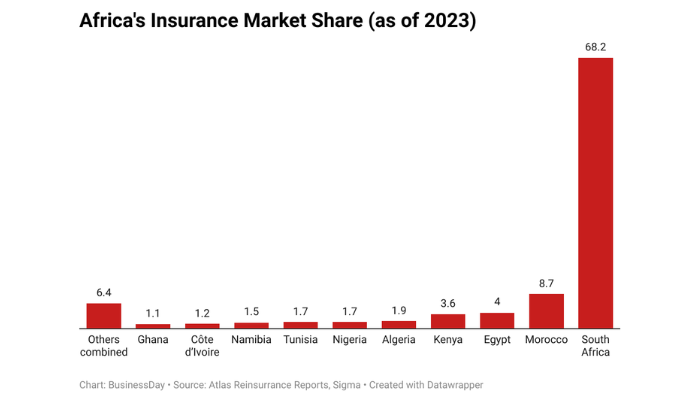

South Africa remains, by far, the dominant figure in the continent’s insurance market as Nigeria accounts for a paltry 1.7 percent of the $63.56 billion share in 2023, underscoring its slow progress in deepening penetration despite its large population and fast-growing economy.

According to data from Atlas Reinsurance Reports and Sigma, Nigeria’s premium volume stood at about $1.08 billion last year, ranking sixth on the continent and tying with Tunisia.

By contrast, South Africa dominated with a staggering 68.2 percent share, roughly $43.36 billion, driven by a mature financial system, compulsory cover policies, and a strong savings culture.

Morocco followed with 8.7 percent ($5.54 billion), while Egypt and Kenya trailed at 4.0 percent ($2.54 billion) and 3.6 percent ($2.29 billion), respectively.

Despite being Africa’s most populous nation, insurance penetration remains below 1 percent of GDP, far behind the continental leader South Africa, where penetration exceeds 13 percent.

The Nigerian insurance sector has, however, shown signs of resilience in recent years. Regulatory reforms by the National Insurance Commission (NAICOM) and the growing adoption of digital platforms are expected to boost uptake, especially among young consumers. Consolidation trends in the industry could also strengthen capacity and competitiveness in a market that has historically been fragmented.

Nigeria’s premium volume of just over $1 billion places it ahead of peers like Namibia ($0.95 billion), Côte d’Ivoire ($0.76 billion), and Ghana ($0.70 billion), but far below its potential relative to the size of its economy and population.

Analysts argue that unlocking Nigeria’s insurance potential will require stronger policy enforcement, wider financial inclusion, and incentives to expand coverage into sectors like agriculture, health, and microinsurance. Without these shifts, Africa’s biggest economy risks remaining a marginal player in a fast-evolving industry.

Domestic growth, continental weakness

Nigeria’s insurers have recorded strong year-on-year gains in naira terms. Gross premiums grew 27 percent in 2023 to N1.003 trillion, up from N790 billion in 2022. Non-life policies made up 61.3 percent of this, or N615.1 billion, while life insurance contributed N388.1 billion. Claims payments also increased, with gross claims reaching N536.5 billion, an indication of rising consumer engagement.

The pace quickened in 2024. By the third quarter, gross premiums had risen to N1.173 trillion, a 60.9 percent increase from the same period a year earlier. Claims payouts surged 89.4 percent to N564.1 billion.

Non-life business led the way, with oil and gas risks, fire, and motor lines accounting for the bulk of premiums. By year-end, total premiums reached N1.562 trillion, a 56 percent jump from 2023, while industry assets expanded to N3.9 trillion.

These achievements, however, mask a harsher reality: when translated into U.S. dollars, Nigeria’s premiums shrank by 31 percent between 2019 and 2023, due to persistent exchange rate weakness. This means the industry’s expansion has been largely nominal, failing to reflect real growth on the continental stage.

Read also: WAICA sees Sanlam Allianz merger deepen insurance market penetration

The penetration gap

Insurance penetration in Nigeria remains one of the lowest in Africa, at just 0.4 percent of GDP. This is a fraction of Kenya’s 2.2 percent and far below South Africa’s 12.2 percent. Even Morocco, with a much smaller economy, records penetration closer to 3 percent.

For many Nigerians, insurance remains either unaffordable or unreliable. Mandatory products such as motor third-party liability are poorly enforced, while confidence in timely claims payments remains weak.

The result is that millions of households and businesses still operate without formal risk cover, leaving the sector underdeveloped relative to its potential.

Reform and opportunity

The National Insurance Commission (NAICOM) has introduced measures to strengthen the industry, including higher solvency requirements, recapitalisation plans, and digital distribution rules.

The regulator is also increasing enforcement of compulsory insurance and pressing insurers to improve claims management. It forecasts that penetration could rise to 2.1 percent by 2033 if reforms are sustained.

Meanwhile, new opportunities are emerging. Partnerships with fintechs and telecoms are widening access to micro-insurance products. Health, agricultural, and takaful (Islamic) insurance are attracting interest, particularly as state governments roll out mandatory health cover. Industry players see these as avenues to broaden insurance culture beyond corporate clients.

Still, challenges remain. Premium affordability, weak enforcement, and poor consumer trust continue to slow progress. Without consolidation, many insurers may remain too small to compete effectively, leaving Nigeria unable to close the gap with peers.

Nigeria remains a paradox in Africa’s insurance landscape. Despite relinquishing its crown as Africa’s largest economy, it remains the continent’s most populous nation. Yet its insurance sector accounts for barely 1.7 percent of Africa’s premiums.

Strong growth in naira terms has failed to translate into regional leadership, leaving Nigeria overshadowed by smaller but more effective markets such as Kenya, with penetration above 2 percent, and Morocco, closer to 4 percent.

Industry analysts argue that the path to relevance lies in stricter enforcement of compulsory policies, faster claims settlements to rebuild trust, and innovation in distribution to reach households and small businesses. Without these shifts, Nigeria’s insurance industry risks remaining a story of local expansion without continental significance.