Nigeria’s economic debate entered a new phase this week after Bismarck Rewane, CEO of Financial Derivatives Company, outlined twelve forces he believes will shape the 2026 outlook, ranging from election-driven spending and tax reforms to a more realistic federal budget and the long-anticipated listing of major national corporations.

His projections, delivered at the Parthian Economic Discourse in Lagos, were followed a day later by an unusually confident assessment from Olayemi Cardoso, Governor of the Central Bank, who told lawmakers in Abuja that Nigeria’s recovery was now “firm and broad-based.”

Together, the two interventions form the clearest picture yet of the kind of economy Nigeria may face in 2026: one defined by steady but unspectacular growth, stabilising prices, firmer financial markets and a long list of structural vulnerabilities that reforms alone cannot instantly resolve.

The new numbers behind the optimism

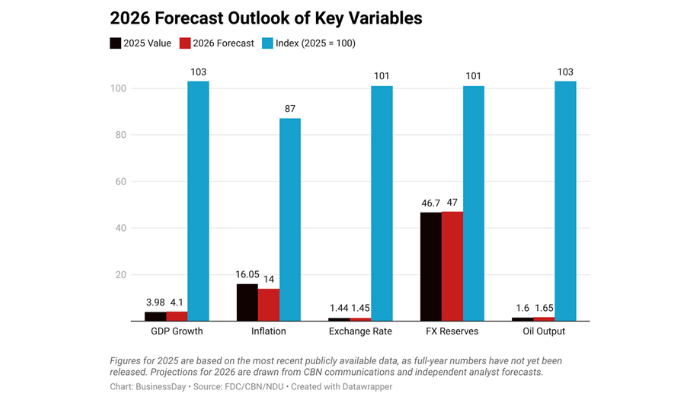

Rewane projects GDP growth of about 4.1 percent in 2026, driven by improved productivity, stronger business activity and rising private investment. This aligns with official sentiment. Cardoso confirmed that GDP grew by 3.98 percent in Q3 2025, the highest for a third quarter in over two years, with ICT, crop production, real estate, and financial services leading the rebound.

Inflation, the pressure point of Nigeria’s recent crisis, has retreated significantly. Headline inflation has fallen from almost 35 percent at the end of 2024 to about 16 percent in late 2025. Food inflation, based on the revised NBS series for October 2025, is reported at roughly 13 percent, reflecting a notable shift from the extreme highs of the previous year.

Foreign-exchange reserves have climbed to $46.7 billion, the highest since 2018, according to CBN data and independent analyst estimates. Diaspora remittances are averaging around $600 million monthly, according to balance-of-payments trackers and market estimates. Capital inflows reached about $21 billion in the first ten months of 2025, nearly 70 percent higher than the full-year 2024 level.

A narrower FX gap, but not a solved problem

Rewane expects the naira to trade between N1,450 and N1,500 next year, supported by higher reserves and fewer arbitrage opportunities. The gap between official and parallel markets has compressed to below 2 percent after exceeding 60 percent last year.

Yet the underlying vulnerabilities remain. Oil prices are forecast to stay below $60 per barrel in 2026, weakening fiscal buffers. Household savings are expected to fall by about N500 billion, signalling consumer strain and the likelihood of sluggish domestic demand.

A reform gap Nigerians will still feel

Nigeria’s stability owes more to tight monetary policy and FX reforms than to big structural change. Inflation has eased partly because demand has been suppressed and liquidity drained from the system, while capital inflows have returned mainly to portfolio assets rather than long-term productive investment.

Fiscal space remains narrow. The proposed 2026 budget, about 10 percent smaller than the current one, reflects discipline but also exposes the limits of government spending power in a low-revenue, high-debt environment, with debt service still absorbing a disproportionate share of federal resources.

Read also: 2026 Outlook: Can tax reforms raise revenue without deepening hardship?

Banks: Stronger, but facing a delicate operating environment

The banking sector enters 2026 from a position of relative strength. Recapitalisation is ahead of schedule, asset quality is improving, and FX-related risks have eased. Lending growth, however, is expected to remain restrained until inflation moderates and monetary policy loosens. High funding costs and weak household and business balance sheets will continue to limit credit expansion, particularly to manufacturing and small enterprises, where subdued demand and operating pressures persist.

Where the risks lie

Three structural fault lines could challenge the optimistic narrative: Insecurity, which continues to disrupt agricultural output and widen regional inequalities; weak oil revenues, with crude output still below potential and global prices forecast to remain soft; and election-year fiscal pressures, which could threaten recent inflation gains if spending becomes expansionary.

The 2026 verdict

Nigeria heads into 2026 with more macro stability than at any point in the past five years. Reforms have calmed markets, narrowed FX gaps and restored a measure of investor confidence. But the next phase will test whether stabilisation can evolve into transformation.

Turning macro gains into jobs, real income growth and industrial competitiveness will depend on political discipline, security outcomes and the ability to channel capital into productive sectors rather than allowing momentum to remain concentrated in finance and services.