When Nigerians queue at bank counters or tap “transfer” on their phones, they believe their deposits fuel the economy, funding small businesses, mortgages, and manufacturing.

But a deep look into the 2025 third-quarter financial statements of the country’s biggest lenders reveals a different reality: only a fraction of customers’ deposits is used to finance the real economy.

The rest is tied up in government securities, pledged assets, or parked as liquidity buffers, the quiet machinery that keeps banks profitable but leaves businesses starved of credit.

The invisible balance-sheet pivot

Across five major lenders, Zenith Bank, Guarantee Trust Holding Company (GTCO), First Bank, Access Bank, and United Bank for Africa (UBA), customer deposits now total well over N110 trillion. Yet less than half of that sits in loans to customers, the core channel through which banks stimulate real‑sector growth.

Read also: Africa Energy Bank ready for takeoff as Nigeria checks off obligations as host country Lokpobiri

A BusinessDay analysis of the publicly released Q3 financial statements on the NGX shows that Nigeria’s largest banks are steadily shifting from traditional intermediation toward balance-sheet management focused on safety, liquidity, and low-risk returns.

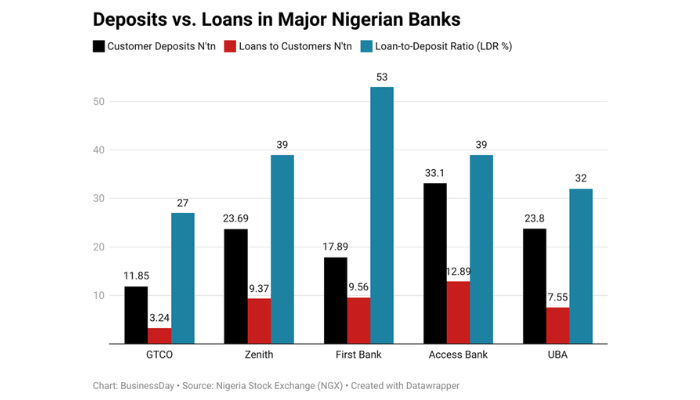

At GTCO, deposits stood at N11.85 trillion as of September 2025. Loans to customers amounted to N3.24 trillion, giving a loan‑to‑deposit ratio of about 27 percent.

The rest of its balance sheet, nearly N4.89 trillion, is invested in government bonds and treasury bills that guarantee stable returns with minimal risk. Pledged assets of N84.1 billion further support market operations but lock away funds that could have reached borrowers.

Zenith Bank, Nigeria’s largest by deposits, tells a similar story with slightly more lending appetite. Customer deposits hit N23.69 trillion, while loans to customers totalled N9.37 trillion, giving a ratio of 39 percent.

The bank’s N4.40 trillion in cash and balances with other banks reflects a deliberate liquidity posture in a volatile market, while its investment securities, historically in double-digit trillions, remain a dominant, low‑risk income source.

Among the other three major lenders, the pattern is consistent. First Bank reports a ratio of 53 percent with N9.56 trillion in loans against N17.89 trillion in deposits. Access Bank, the largest by asset size, records a lower 39 percent, with N12.89 trillion in loans out of N33.10 trillion in deposits. UBA trails further, lending out only N7.55 trillion from N23.80 trillion in deposits, a ratio of about 32 percent.

“A deposit in the bank no longer guarantees that someone else’s business will grow. Instead, it often fuels the government’s borrowing needs, a paradox where Nigerians’ savings finance the same public debt that crowds out their own access to finance.”

How the numbers add up

In simple terms, for every N100 Nigerians deposit in these five banks, only about N40 goes into loans. The rest is recycled into government debt or parked in liquidity and trading assets.

By comparison, banks in emerging economies such as India and Brazil typically lend a much larger share of deposits, with loan-to-deposit ratios of 85 percent–96 percent and 91 percent, respectively, showing that Nigerian banks are more conservative in allocating deposits to the real economy.

“Many states and banks choose safety over growth, and depositors are paying the price. When banks park deposits in government paper, the private sector is starved of credit that would create jobs and expand firms,” said Muda Yusuf, Chief Executive, Centre for the Promotion of Private Enterprise.

This pattern reflects deeper structural issues in the financial system. According to Ayo Teriba, CEO of Economic Associates, “Nigeria should securitise public assets to unlock liquidity and boost domestic capital markets.” Teriba argues that unless this is done, the banking system will remain skewed toward financing government deficits.

Profit without risk

To the banks, the model works beautifully. The five lenders collectively reported tens of trillions in interest income this year, much of it from risk-free instruments. Securities portfolios, particularly those held at amortised cost or measured at fair value through other comprehensive income, now dwarf loan books in size and contribution.

Analysts say it is a rational survival strategy. “When inflation and currency risk are this high, lending to the government is safer and more profitable than lending to the private sector,” said Oluwatobi Abisoye, a financial analyst.

There is broad concern about the “crowding-out effect” of this strategy. The Nigerian Association of Chambers of Commerce, Industry, Mines and Agriculture (NACCIMA) warned recently that excessive public-sector borrowing from banks is constraining access to credit for businesses.

Last year, in a letter to both the Minister of Finance and the Governor of the Central Bank, NACCIMA said that “private sector entities are currently facing exorbitant barriers to accessing finance” because government borrowing absorbs so much of the banking sector’s capacity.

The cost to the economy

For the wider economy, however, the implications are sobering. Nigeria’s private‑sector credit‑to‑GDP ratio remains among the lowest in peer emerging markets. Small businesses face high rejection rates, while manufacturers are squeezed by interest rates often north of 25 percent.

The ripple effect is visible everywhere: sluggish job creation, weak industrial output, and rising dependency on government spending to drive growth.

A deposit in the bank no longer guarantees that someone else’s business will grow. Instead, it often fuels the government’s borrowing needs, a paradox where Nigerians’ savings finance the same public debt that crowds out their own access to finance.

Read also: Why Fidelity Bank hit the brakes on dividend payments in H1 2025

The paradox of safety

The five-bank data paint a clear picture. Nigerian banking has become safer, more liquid, and immensely profitable but also less connected to productive enterprise. In shielding themselves from risk, banks may have inadvertently shielded the economy from growth.