By Ebuka Ukoh

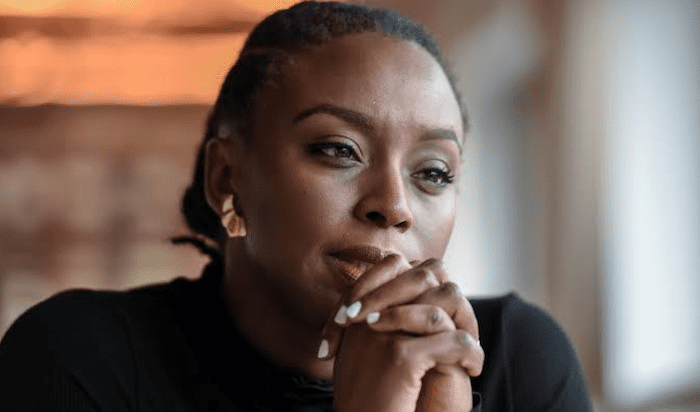

Nigeria has opened a probe into the death of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s infant son, who was three months shy of two years.

The Lagos State Government, in whose jurisdiction the death occurred on January 6, 2026, states that it is investigating the incident at Euracare Hospital. The Lagos governor has offered condolences, committees have been named, and statements have been issued.

I am not impressed.

Not because a probe is wrong, but because of what it reveals. We did not need a world-renowned writer to lose a child to discover that our systems are broken. We already have the data. Nigeria ranks among the countries notorious for infant and under-five mortality. Thousands of Nigerian parents bury their dead quietly every year. They cry without hashtags. They grieve without cameras. They disappear back into daily survival without headlines, press statements, or probe panels.

Yet it took a global name, a voice the world already listens to, for the machinery of official concern to roar to life suddenly.

We saw the same choreography recently in the public handling of boxer Anthony Joshua road crash. A fatal accident took lives, yet the first national reflex was not structural interrogation but image management. Press statements arrived faster than safety audits. Branding anxieties surfaced before institutional accountability. What the moment quietly exposed was not only grief but also how fragile our emergency response systems remain. From roadside hazard management to trained trauma response, Nigerians again saw confusion where there should have been protocol. It was another reminder that in our country, tragedy too often becomes performance before it becomes reform.

That is not compassion. That is theatre.

I am not yet a biological father. But my life changed the day my brother and his wife welcomed and named their firstborn son after me. It altered my sense of responsibility, of vulnerability, of what it means to love someone whose safety you cannot fully control. I will save that story for another day. I can affirm that the love of a parent is fierce, consuming, protective, and sacred.

I have watched my mother raise three children. I now watch my sister-in-law love her two sons with a devotion that rearranges both hers and her husband’s lives daily. From this vantage, I know the love of a parent for a child is proportional to the pain they feel when that child dies. And when death is avoidable. When a duty of care was owed. When systems failed. When standards collapsed. The grief becomes heavier. The questions become louder. The wound becomes political.

It is with that burden that my heart broke when I first read about the death of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s son. It shattered further when the reported circumstances suggested what every Nigerian already knows too well. That in our country, systems fail people in their most vulnerable moments. Those standards are uneven. That regulation is weak. That accountability is selective.

No parent should endure this.

But something even more dangerous is happening in Nigeria today. We are slowly being trained to accept the unacceptable. To normalise what should outrage us. To believe that justice depends on who you are, not what happened. To believe that your child’s life becomes more valuable when the world already knows your name.

That is how nations decay.

This moment is bigger than one family, even though we must honour their grief with deep reverence. It is bigger because what failed here is not unique. It fails daily in maternity wards, paediatric units, private clinics, public hospitals, and roadside emergencies across the Federation.

And yet Nigerians still rise.

Mothers still line up at clinics. Fathers still borrow money for treatment. Nurses still show up as underpaid. Doctors still work in collapsing systems. Citizens still hope.

Our victory has never been individual. It has and will always be collective.

We do not win because one family gets justice. We win when systems change. We win when standards rise. We win when every Nigerian child has the same right to life, care, and protection, whether their parents are famous or unknown.

We must not lose hope. But hope is not passive. Hope organises. Hope speaks. Hope demands better. Hope refuses to normalise pain.

When one child dies in preventable circumstances, a nation is on trial.

This is that trial.

May God comfort the Adichie family. May He strengthen their hearts. And may their loss become a turning point that forces Nigeria to finally confront what we have tolerated for far too long.