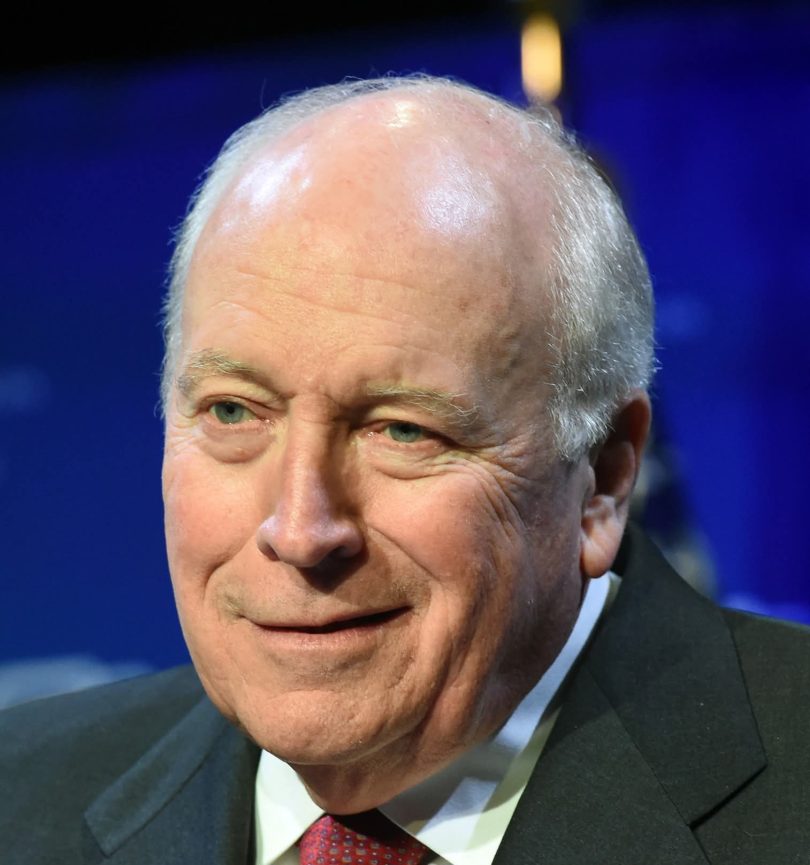

Dick Cheney, the hard-charging conservative who became one of the most powerful and polarizing vice presidents in U.S. history and a leading advocate for the invasion of Iraq, has died at age 84.

Cheney died Monday due to complications of pneumonia and cardiac and vascular disease, his family said Tuesday in a statement.

“For decades, Dick Cheney served our nation, including as White House Chief of Staff, Wyoming’s Congressman, Secretary of Defense, and Vice President of the United States,” the statement said. “Dick Cheney was a great and good man who taught his children and grandchildren to love our country, and to live lives of courage, honor, love, kindness, and fly fishing.”

The quietly forceful Cheney served father and son presidents, leading the armed forces as defense chief during the Persian Gulf War under President George H.W. Bush before returning to public life as vice president under Bush’s son George W. Bush.

Cheney was, in effect, the chief operating officer of the younger Bush’s presidency. He had a hand, often a commanding one, in implementing decisions most important to the president and some of surpassing interest to himself — all while living with decades of heart disease and, post-administration, a heart transplant. Cheney consistently defended the extraordinary tools of surveillance, detention and inquisition employed in response to the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

Bush called Cheney a “decent, honorable man” and said his death was “a loss to the nation.”

“History will remember him as among the finest public servants of his generation — a patriot who brought integrity, high intelligence, and seriousness of purpose to every position he held,” Bush said in a statement.

Years after leaving office, Cheney became a target of President Donald Trump, especially after his daughter Liz Cheney became the leading Republican critic and examiner of Trump’s desperate attempts to stay in power after his 2020 election defeat and his actions in the Jan. 6, 2021, riot at the Capitol.

“In our nation’s 246-year history, there has never been an individual who was a greater threat to our republic than Donald Trump,” Cheney said in a television ad for his daughter. “He tried to steal the last election using lies and violence to keep himself in power after the voters had rejected him. He is a coward.”

In a twist the Democrats of his era could never have imagined, Cheney said last year he was voting for their candidate, Kamala Harris, for president against Trump.

A survivor of five heart attacks, Cheney long thought he was living on borrowed time and declared in 2013 he awoke each morning “with a smile on my face, thankful for the gift of another day,” an odd image for a figure who always seemed to be manning the ramparts.

In his time in office, no longer was the vice presidency merely a ceremonial afterthought. Instead, Cheney made it a network of back channels from which to influence policy on Iraq, terrorism, presidential powers, energy and other cornerstones of a conservative agenda.

Fixed with a seemingly permanent half-smile — detractors called it a smirk — Cheney joked about his outsize reputation as a stealthy manipulator.

“Am I the evil genius in the corner that nobody ever sees come out of his hole?” he asked. “It’s a nice way to operate, actually.”

The Iraq War

A hard-liner on Iraq who was increasingly isolated as other hawks left government, Cheney was proved wrong on point after point in the Iraq War, without losing the conviction he was essentially right

He alleged links between the 2001 attacks against the United States and prewar Iraq that didn’t exist. He said U.S. troops would be welcomed as liberators; they weren’t.

He declared the Iraqi insurgency in its last throes in May 2005, back when 1,661 U.S. service members had been killed, not even half the toll by war’s end.

For admirers, he kept the faith in a shaky time, resolute even as the nation turned against the war and the leaders waging it.

But well into Bush’s second term, Cheney’s clout waned, checked by courts or shifting political realities.

Courts ruled against efforts he championed to broaden presidential authority and accord special harsh treatment to suspected terrorists. His hawkish positions on Iran and North Korea were not fully embraced by Bush.

Cheney operated much of the time from undisclosed locations in the months after the 2001 attacks, kept apart from Bush to ensure one or the other would survive any follow-up assault on the country’s leadership.

With Bush out of town on that fateful day, Cheney was a steady presence in the White House, at least until Secret Service agents lifted him off his feet and carried him away, in a scene the vice president later described to comical effect.

Cheney’s relationship with Bush

From the beginning, Cheney and Bush struck an odd bargain, unspoken but well understood. Shelving any ambitions he might have had to succeed Bush, Cheney was accorded power comparable in some ways to the presidency itself.

That bargain largely held up.

As Cheney put it: “I made the decision when I signed on with the president that the only agenda I would have would be his agenda, that I was not going to be like most vice presidents — and that was angling, trying to figure out how I was going to be elected president when his term was over with.”

His penchant for secrecy and backstage maneuvering had a price. He came to be seen as a thin-skinned Machiavelli orchestrating a bungled response to criticism of the Iraq War. And when he shot a hunting companion in the torso, neck and face with an errant shotgun blast in 2006, he and his coterie were slow to disclose that extraordinary turn of events.

The vice president called it “one of the worst days of my life.” The victim, his friend Harry Whittington, recovered and quickly forgave him. Comedians were relentless about it for months. Whittington died in 2023.

When Bush began his presidential quest, he sought help from Cheney, a Washington insider who had retreated to the oil business. Cheney led the team to find a vice presidential candidate.

Bush decided the best choice was the man picked to help with the choosing.

Together, the pair faced a protracted 2000 postelection battle before they could claim victory. A series of recounts and court challenges left the nation in limbo for weeks.

Cheney took charge of the presidential transition before victory was clear and helped give the Republican administration a smooth launch despite the lost time. In office, disputes among departments vying for a bigger piece of Bush’s constrained budget came to his desk and often were settled there.

On Capitol Hill, Cheney lobbied for the president’s programs in halls he had walked as a deeply conservative member of Congress and the No. 2 Republican House leader.

Jokes abounded about how Cheney was the real No. 1 in town; Bush didn’t seem to mind and cracked a few himself. But such comments became less apt later in Bush’s presidency as he clearly came into his own.

Cheney’s political rise

Politics first lured Dick Cheney to Washington in 1968, when he was a congressional fellow. He became a protégé of Rep. Donald Rumsfeld, R-Ill., serving under him in two agencies and in Gerald Ford’s White House before he was elevated to chief of staff, the youngest ever, at age 34.

Cheney held the post for 14 months, then returned to Casper, Wyoming, where he had been raised, and ran for the state’s lone congressional seat.

In that first race for the House, Cheney suffered a mild heart attack, prompting him to crack he was forming a group called “Cardiacs for Cheney.” He still managed a decisive victory and went on to win five more terms.

In 1989, Cheney became defense secretary under the first President Bush and led the Pentagon during the 1990-91 Persian Gulf War, which drove Iraq’s troops from Kuwait. Between the two Bush administrations, Cheney led Dallas-based Halliburton Corp., a large engineering and construction company for the oil industry.

Cheney was born in Lincoln, Nebraska, son of a longtime Agriculture Department worker. Senior class president and football co-captain in Casper, he went to Yale on a full scholarship for a year but left with failing grades.

He moved back to Wyoming, eventually enrolled at the University of Wyoming and renewed a relationship with high school sweetheart Lynne Anne Vincent, marrying her in 1964. He is survived by his wife, by Liz and by a second daughter, Mary.